Within this Training Course in March 2013 supported by the EU’s Youth in Action Programme, Ingo Nordmann had the chance to talk to young people, officials at the municipality, and different activists to find out how young people in this region evaluate the situation and what the government and NGOs are doing to change it.by Ingo Nordmann, nordmann.ingo@gmail.com

“If you’re 28 years old, with two university degrees, and your parents have invested all their money in your education, and you’ve done everything that was expected of you: if society then tells you, ‘sorry, we don’t have a job for you’, then it’s easy to understand why people revolt. We have to give young people hope. In Europe, the world’s richest continent, there has to be a place for young people, damn it!”1

With these words, Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament, describes the heart of the problem. Most young, unemployed Europeans are not marginalized, deprived, and lazy, but they live in the centre of society – a society that seems to have no use for them. In Germany, as in other countries, graduates, especially those of the social sciences and humanities, are disillusioned with their perspectives on the job market. While it is true that finding a job is not easy and the often-cited “Generation Internship”2 is definitely struggling, the discussion may have become a little out of proportion – doesn´t the graduates’ collective pessimism prevent them from going where they want to go? In fact, Germany has the lowest youth unemployment rates of all EU countries, down from 14% in 2004 to 8% in 2012.3

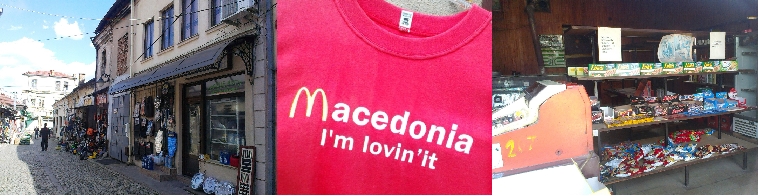

That looks paradisiacal compared to percentages of over 50% in some Southern European countries such as Greece and Spain. Youngsters from countries outside of the EU face even more severe challenges on the job market. To put the worries of current German graduates into perspective, I gathered some impressions from the beautiful, but often-neglected Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. During a training course supported by the EU’s Youth in Action Programme, YMCA Bitola (www.ymcabitola.org.mk), and Culture goes Europe – Soziokulturelle Initiative Erfurt (http://www2.cge-erfurt.org), I had the chance to talk to young people, officials at the municipality, and activists at the Business Start-up Centre Bitola, to find out how young people in this region evaluate the situation and what the government and NGOs are doing to change it.

Particularly impressive for me was the young people’s high motivation and their flexibility to cope with different situations and work with different people. Out of 22 people, 16 would immediately be willing to move to a different country to take up a job. Another four were willing to move to a different city. This flexibility is probably one of this generation’s greatest assets.

At the same time, I noticed a great deal of pessimism regarding the prospect of working in a Western European country. A majority (65%) thought that in most cases, migrants could only find low-skill jobs and that there was a general lack of respect for foreign workers in Western European countries. One participant from Kosovo readily told the story of his aunt, who had worked as a lawyer in Kosovo before the war and now has a job as a cleaning lady in France. But such a situation not only occurs after migration: The cleaning lady in our hotel in Trnovo had been trained as an architect, but in the face of poor perspectives in the Macedonian job market took up a job as a maid.

One of the main criticisms young people had, irrespective of their nationality, was that the educational system often does not adequately prepare them for the demands of the labour market. They argue that educational systems, both secondary and tertiary, need to be thoroughly changed and adapted. They plead for the integration of more practical experience into education, for better career advice in schools and universities, and for opportunities to improve soft skills, IT knowledge, and foreign languages. They demand that schools and universities provide more detailed information about the situation on the job market, as well as advice on how to write applications and succeeding in interviews. These are things which could be changed by governments and be supported by NGOs.

Remarkably, the participants themselves demand fair assessments of their qualifications (university degrees etc.) in potential host countries. Thus, the widespread argument of Western countries that diplomas from countries outside of the EU are “just not comparable to ours” is invalidated. Young people from all over Europe understand that university diplomas from different countries are not in all cases equivalent and need to be assessed before being accepted.

What young people do complain about repeatedly, however, are the strict visa regulations of the EU. Youngsters demand more liberal regulations, enabling them to travel and move to other countries without disclosing their entire family history. Another demand came from Macedonian participants: starting your own business should be made easier and supported by the state. In Bitola this is currently being done at the Business Start-up Centre Bitola (BSCB) – a place I am going to talk about later. But first, it was time to ask officials at the municipality what they actually intend to do for young people in the area.

It was election time in Bitola – large portraits of the candidates were everywhere in the city, adorned with the all-too-modern Like-buttons and a Facebook link. The current Mayor of Bitola, Vladimir Taleski, a popular former actor, was re-elected. Young Macedonians, however, did not seem to be too interested in the outcome of the elections anyway. They do not believe that change was going to come from the current government, now serving its third term. “It´s like the new Pope – you’d expect change, but it’s more of the same, really”, says one. The unemployment rate in Macedonia has stagnated at over 30% for the past 10 years, reaching 31% in 2012.4 Among people aged between 15 and 24, the rate is 55%.5 That excludes many young people’s considerable under-employment.

At the town hall, pictures of the pretty city centre and the flag of the EU decorate the walls. You can tell that it is supposed to look official. While the rooms are clean and tidy, they also seem a bit empty. Mr Pandev of the municipality was very warm and welcoming. Confronted with students’ allegations that a lot of money still disappears under mysterious circumstances, he chuckles, “Of course there are examples of corruption, but the situation has become much better over the last years”. He speaks of successes in recent years and the need for an optimistic view of the future. When asked what exactly the municipality does to empower the youth and to fight the high unemployment rates, he points to organizations the government supports, such as the Business Start-up Centre Bitola.

“But with a collective memory of socialism in people’s minds, it is extremely difficult to manage the tough transfer to capitalism and at the same time avoid damage at the social level.” Too many young people may have too little initiative. While the socialist system severely limited personal freedom, it also meant that many basic needs (e.g. employment and housing) were provided “from above”. Therefore, Mr Pandev suggests, many youngsters lack the attitude and motivation to initiate change themselves.

Instead, many Macedonian university graduates want to secure a job in public administration – according to one student, these jobs represent long-term financial security and social status in exchange for comparatively little work. Obviously, this spirit is not conducive to vitalizing the economy. During the current Euro crisis, discussions about the decline of capitalism are at an all-time high in Western Europe, but a little more of an unapologetically capitalist spirit would probably help Macedonia come to terms with the post-socialist constitution of its economy. Or, as Mr Pandev puts it, “You are young now! Change something before you get married, get fat, and become a part of the system”. An organization that actively tries to implement this is the Business Start-Up Centre Bitola – our next stop.

The BSCB’s (www.bscbitola.org) goal is to accelerate economic growth in Southwestern Macedonia by helping young people to find a job or start a business themselves. Their modern, tidy offices, just a few hundred metres from the main square, smell of fresh paint. They also include some shared office space, which young Graphic designers and software engineers use in turns – a cost-effective alternative to renting one’s own place, as well as an opportunity for networking.

BSCB is supported by the United States Agency for International Development (US AID). Joe, an American volunteer in his 60s, welcomes us and introduces himself with the words “I am from Atlanta, Georgia, and I started the Coca-Cola company”. His positive, optimistic spirit is contagious. “My wife wasn’t particularly happy when I told her that I was going to the Balkans to volunteer. But in a few weeks she’s coming to visit me. People here are extremely motivated and capable, all they need is some advice and infrastructure. And their English is excellent. I am still struggling with saying hallo in Macedonian.”

Joe goes on to explain why it is important to focus on small and medium-sized businesses. “Many towns think that smoke stag chasing is the way forward.” He means the attempts by cities to attract large corporations, which will then build factories with giant chimneys in the vicinity. Also in Bitola, the single largest employer is the big power plant on the outskirts of the city. But 90% of new jobs in the region, Joe emphasizes, actually come from new start-ups, small businesses and their growth. BSCB therefore facilitates the start-up of new enterprises with micro credits of up to 15,000 Euro. They may also help by refunding registration fees of new companies, assisting with accountancy, setting up a website, and designing logos. They provide business-skills trainings, e.g. about social media marketing or finances, and enable young start-ups to present themselves at trade fairs in Skopje, Sofia, or Belgrade.

BSCB has achieved some great successes in recent years. Between 2011 and 2013, about 180 companies have been supported by the organization, and 378 new jobs were created in Bitola alone. In 2012, more than 1000 young people participated in business-skills trainings supported by BSCB. “We’ve done a lot, but there is much more to be done in the future”, Joe says. While he is going to return to his home in the US at the end of the year, the organization will continue to support young people motivated to take up responsibility and change their situation.

The potential for improvement is there: Macedonia has profited from relatively stable, albeit modest economic growth in recent years.6 The fact that the youth, especially outside of the capital Skopje, does not yet benefit from this growth suggests that structural problems are to blame. As youth unemployment rates are twice as high as the overall unemployment rate, it seems that socioeconomic policies have hitherto favoured older generations and focused on maintaining existing jobs, rather than developing new ones. Now, the youth is paying the price.

The fight of organizations such as BSCB is going to be a long one – but at least, they have started.

You can follow Ingo’s blog on

http://governancexborders.com/

1 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/elisabeth-braw/european-parliament-presi_b_2924056.html?utm_hp_ref=tw

2 Der Spiegel title story, 31/2006

5 http://www.indexmundi.com/g/r.aspx?v=2229, http://www.onlinecolleges.net/2012/05/28/10-countries-with-the-worst-youth-unemployment-problems/

6 Around 3% in 2011 and 2010, CIA Factbook